Background: Bleeding is a major complication of intensive AML induction therapy that has been linked to increased early mortality. Identifying patients with increased bleeding risk could improve outcomes by allowing development of preventative strategies. Prior studies have focused on clinical trial or registry cohorts to identify factors associated with bleeding outcomes, and may not reflect typical clinical practice or have adequately detailed clinical or genetic data. Therefore, we sought to define the incidence and distribution of bleeding in a real-world cohort of AML patients and determine which pretreatment clinical, laboratory and genetic factors were associated with bleeding.

Patients and methods: We identified 341 consecutive adult patients with newly diagnosed AML who received anthracycline-based induction chemotherapy. The median age was 61 years (range 19-79). Diagnostic samples from all patients were sequenced for recurrently mutated myeloid genes. We collected pretreatment clinical and laboratory data, and annotated bleeding events during the first 60 days of treatment according to the WHO bleeding assessment scale. Bleeding was classified as clinically significant if WHO grade ≥2, or grade 1 if it prompted a change in platelet transfusion threshold. Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) was assessed using a modified ISTH DIC-score including platelet count, PT-INR, and fibrinogen, where a score ≥3 points indicates high risk of DIC. D-dimer was excluded due to missing data.

Results: A total of 87 patients (26%) had clinically significant bleeding events, most commonly involving gastrointestinal (n=35), genitourinary (n=31), and central nervous system [CNS (n=12)] sites. Patients with clinically significant bleeding events had worse survival within the first 60 days of induction treatment compared to patients without clinically significant bleeding (HR 5.24; 95% CI: 2.50-10.96, P < 0.001).

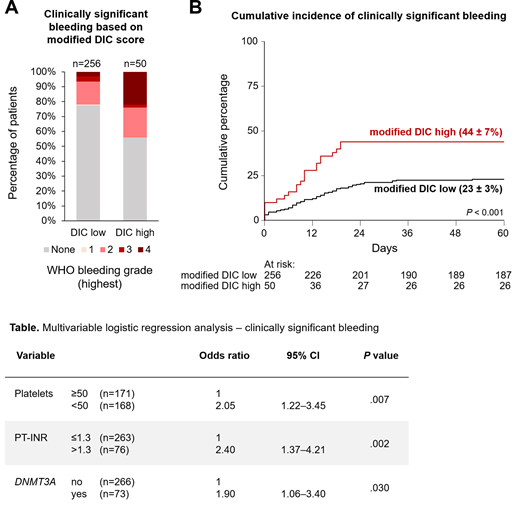

The incidence of clinically significant bleeding was higher among patients with a high pretreatment modified DIC score compared to those with a low modified DIC score (44% vs. 24%, P = 0.002, Figure A-B). This difference was most prominent among patients with WHO grade 4 bleeds (22% vs. 3%, P < 0.001, Figure A). Most clinically significant bleeding events (n=57) occurred within the first two weeks of induction treatment (Figure B). Using multivariable logistic regression analysis, we found that pretreatment platelet count <50 x 109/L, PT-INR >1.3, and the presence of a DNMT3A mutation were independently associated with bleeding within the first 60 days of AML induction treatment (Table). Other factors previously linked with bleeding risk, including age, sex, hepatic and renal function, and leukocyte count, were not associated with an increased risk of bleeding in this cohort.

Early mortality was particularly high (58%) in patients who experienced a CNS bleed, which events included intraparenchymal and/or subdural hemorrhage (n=9), and hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic stroke (n=3). Two thirds (n=8) of patients with CNS bleeds had high pretreatment modified DIC scores. Using univariate regression analysis, we found that the presence of DNMT3A or TET2 mutations had significantly increased odds ratios for CNS bleeds (3.84; 95% CI: 1.20-12.2 and 4.18; 95% CI: 1.27-13.71, respectively). The frequency of CNS bleeds was significantly higher amongst patients with DNMT3A and/or TET2 mutations compared to patients without these mutations (8% vs. 1%, P = 0.004).

Conclusions: The incidence of bleeding in this real-world cohort of AML patients receiving intensive induction chemotherapy was higher than previously reported in selected clinical trial cohorts. Clinically significant bleeding during initial induction was associated with poor short-term survival. Low platelet count, elevated PT-INR and DNMT3A mutations were independently associated with clinically significant bleeding. The incidence of CNS bleeds was highest in patients with DNMT3A or TET2 mutations, and rare in patients without these mutations, raising the possibility that genetic events driving early leukemogenesis may exert pleiotropic effects that impact hemostasis. Together, these results identify a subset of AML patients who may benefit from additional supportive care measures to prevent early bleeding associated with morbidity and mortality of intensive induction treatment.

Wolach:Amgen: Other: Fees for lectures and Consultancy; Janssen: Other: Fees for lectures and Consultancy; Astellas: Consultancy, Honoraria, Other: Fees for lectures and Consultancy; AbbVie: Consultancy, Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Other: Fees for lectures and Consultancy, Research Funding; Pfizer: Consultancy, Honoraria; Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria, Other: Fees for lectures and Consultancy. Neuberg:Celgene: Research Funding; Madrigak Pharmaceuticals: Current equity holder in publicly-traded company; Pharmacyclics: Research Funding. Lindsley:MedImmune: Research Funding; Takeda Pharmaceuticals: Consultancy; Jazz Pharmaceuticals: Consultancy, Research Funding; Bluebird Bio: Consultancy.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal